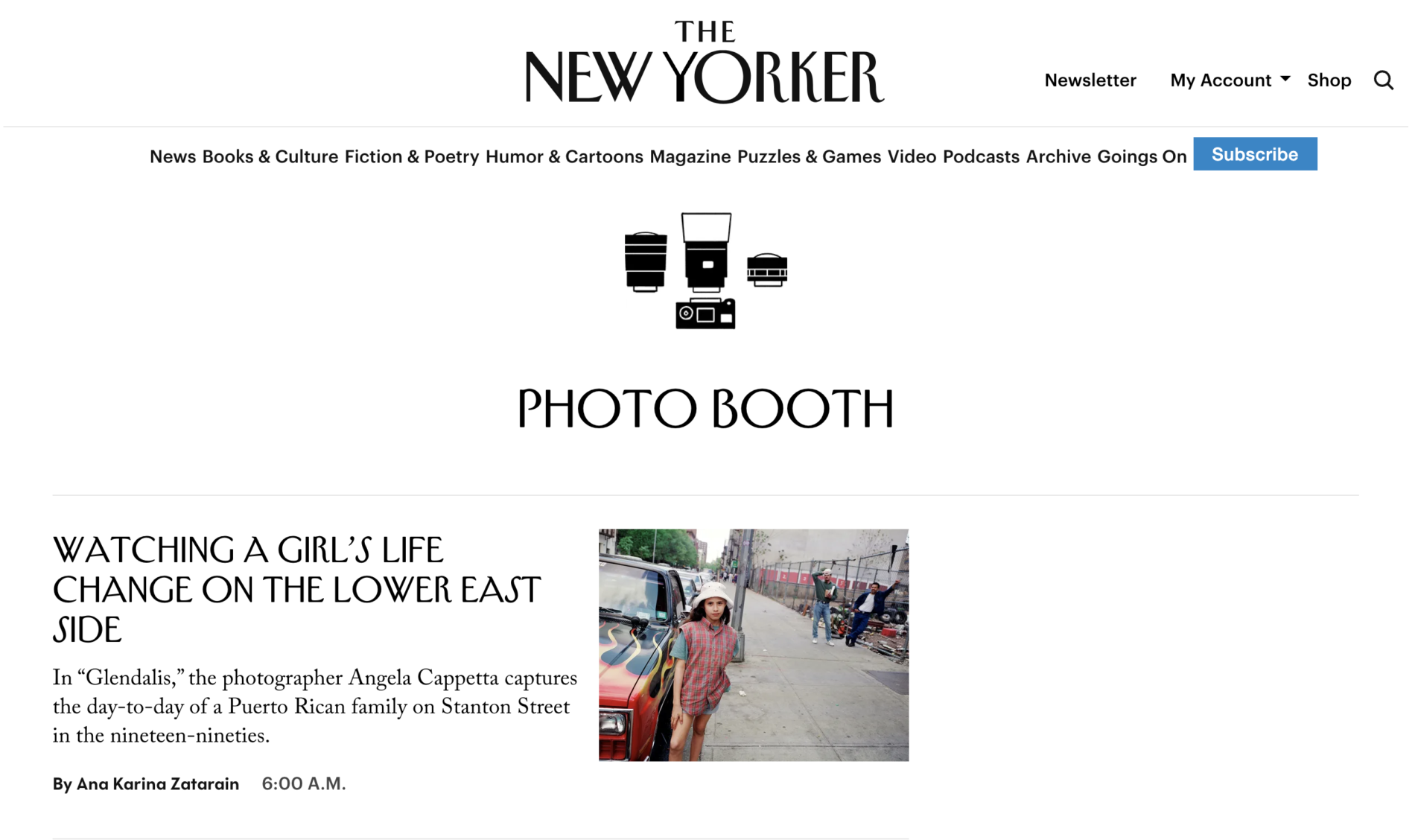

The young girl is standing on the edge of the street, between the sidewalk and a black car. Red-and-yellow airbrushed flames crawl up its hood. With one knee jutting forward and a hand resting just above it, she appears to be trying confidence on for size. Behind her, at a distance, two men stand next to the faltering fence of a vacant lot, empty but for some urban debris—the kind of derelict sliver of land that has largely disappeared from Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where this photograph was taken, in the late nineteen-nineties.

The neighborhood was different then. During those years, just before a fierce wave of gentrification hit the area, the photographer Angela Cappetta often rose at dawn to roam the streets, a Fuji 6x9 camera in hand. (“I still use it,” she told me. “It looks fake, like a toy.”) It was on one of those mornings that Cappetta encountered a clan that reminded her of her own upbringing, within a multigenerational family of Italian immigrants, in Connecticut. As a child, Cappetta was shepherded among various homes by aunts, uncles, and older cousins—a constant and frenetic flow of relatives. The family she met that day, Puerto Rican New Yorkers living on multiple floors of a tenement building on Stanton Street, had a similar dynamic. Instinctively, she began placing each member in their role. “I looked at this beatific, beautiful family, and I thought, Yeah, I relate to this,” she recalled.

Though she had no clear intention when she started to photograph them, eventually, a theme emerged: the sort of exchanges that unfold among generations coexisting in intimate proximity and communion. “I was after the big picture of how someone fits into a family, and how everybody in that family is adapting and developing in ways that are either visible or invisible,” Cappetta told me. But projects that unfold over years inevitably undergo transitions themselves; a different story can surface, take things in a new direction. Among the family members Cappetta began photographing was a nine-year-old named Glendalis, the youngest of three sisters. Her father lived in an apartment below her, and her grandmother in an apartment below him. Perhaps because the passage of time through a body and psyche is never more potent and visible than in childhood and adolescence, Glendalis emerged as the nucleus of the photo series; the people who orbited her throughout that period became supporting characters. Eventually, the series took her name.

In one photograph, we see her draped over the back of an armchair occupied by her grandmother, her eyes closed and her face upturned, catching the single ray of sunshine that enters a dim room. An oversized T-shirt engulfs her, a plastic tiara sits on her head, bunny slippers cover her feet. We see her on the street, with dark and untamed curls cascading down her back or shoulders. Suddenly, she is taller and older; her brows have been plucked into thin arches. Her father looks into the camera as she sits in the background, glancing over her shoulder; she stands in the corner of a kitchen, seemingly half engaged in schoolwork. A particularly tender and solemn picture shows three girls gathered above her, cradling strands of her hair as they unbraid them, a depiction of kinship and the rituals embedded into womanhood.

One might see in these photos a coming of age, but Cappetta rejects that label; her subject’s unfolding maturity was less significant, she says, than the larger themes of family and community, the relationships that a person nurtures, and how they transform along with them through time. Looking back on her own adolescence, Cappetta recognizes parallels between her life and what she documented in this series. Both she and Glendalis were the youngest girls in their families, and were always shuffling from one relative’s home to another’s. But Cappetta says that her status as an outsider shaped the project as much or more than the personal connections she found. “I’ve been shooting my own family for decades, and the photos look nothing like these,” she said. Distance was clarifying, in a way. Glendalis and her family opened their lives to Cappetta, allowing the camera to serve not as a mirror but a window.

.png?format=original)